FEATURED

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

The Pioneer Park Basketball League

He fails to mention that shelters have curfews. People leave the park not because they’re done "loitering" — but because they know they’ll lose their bed and meal if they don’t check in on time.

Now that I’m living near the park and connected not just by proximity but by community, I find those blind takes misguided.

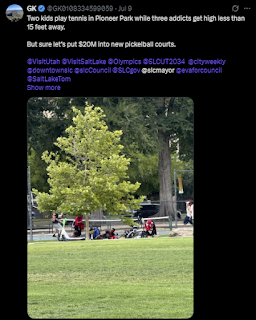

For the past few weeks, around 6 p.m., I’ve walked over to the basketball courts. Yes, the ones surrounded by drug users and schizophrenic yellers who scare everyone off. I shoot around for hours. And I invite the same people in those Twitter photos to play with me.

And I’m probably the only one out there giving them real, human interaction. I’m not volunteering through a religious nonprofit. I’m not a cop patrolling the area. I’m just a guy with a $2 thrift-store basketball and a peeling grip.

When someone asks to use my phone, I’ll tell them they have to shoot for it. That usually gets a smile. At least once a week, I round up enough people for a proper 2-on-2 game to 11. It takes forever — we’re all bad shooters — but it’s not about the game. It’s about giving them something that maybe they haven’t felt in a long time: humanity. Equality. A break.

A lot of them are kids or young adults. I don’t ask their stories unless they bring them up. I don’t pry. On the court, we’re just people. And I like to think they feel that too.

The guy on Twitter doesn’t have a problem with Pioneer Park. He has a problem with systemic poverty. With addiction. With mental illness. With the way our city avoids confronting any of it.

There are about ten shelters around the Rio Grande area. None are run by the LDS Church or the city. Most are run by Christian or Catholic organizations, or by private foundations named after someone’s last name. Some offer case management. Some just offer a bed and food. Sometimes clothing when it gets cold.

Most of them are just waiting out the clock until their shelter opens again. They have nowhere else to go. They’ll always be misunderstood, because most people can’t even imagine ending up in that position. But they have mental health issues. Physical injuries. No family. A long list of things that would break most of us, and yet they’re still trying to survive.

It’s not fair to judge the quality of a city based on how visible the homeless population is. The real issue isn’t that you can see them. The issue is that you do see them, and still do nothing.

Pioneer Park is just two blocks away from the Delta Center, surrounded by flashy development for sports fans and the wealthy. A $20 million facelift is great for a public amenity, but it won’t fix what this guy — and the rest of the city — thinks is a problem. Because it’s not a problem you fix with money. It’s a mindset.

Utah has an anti-safety-net mentality. It’s this quiet belief: If we don’t give them services, maybe they’ll just go away.

But the truth is, with the way the world’s headed, this population is only going to grow.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps